THE FEAR

“Startled, I awoke as my heart pounded, my eyes grew wide in fear, ‘…will they understand why I am presenting marble over polished concrete, or why I am recommending steel so reflective it appears transparent, or even get why blond wood is an applicable option…’ The fears would not subside and it felt like hours before I drifted back to sleep.”

INTRODUCTION

Stories are tools used to create conversations, evoke emotion, and provide a common ground between people. In architecture stories are used to communicate between the architect, client, and the public. By analyzing the effect storytelling has in architecture, we can better understand its value and how it is used effectively across project types. Storytelling affects the success of a firm, architect or project. Several elements which contribute to successful storytelling are acknowledging who the audience is, understanding the moral of the story in relationship to the audience, and the clarity of communication or how well these points are communicated to the audience. For example, the Nelson Atkinson Museum addition was a blind competition in which Steve Holl’s proposal was chosen (Steven Holl 2017). Holl’s story captivated his audience because he understood what they wanted to tell and designed it in a way that supported it, even though it was the opposite of what they had asked for. He used storytelling to capture their imagination and enable them to think outside the box. The American Folk Art Museum by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien is an example of using storytelling to gain trust of their client (Karrie Jacobs 2017). They wanted to understand the client’s and users needs of the building. Tod Williams Billie Tsein has a firm philosophy that governs how they respond to the client. Space Calculated in Seconds is a book describing the process of building the Philips Pavilion, and showing various forms of communication throughout the process (Marc Treib 1997). Analyzing storytelling is challenging because it is hard to quantify, however, there are many stories that serve as good examples. This paper is important because if people do not understand the storytelling process, they will not understand the importance of how architects have arrived at their solutions and they will miss out on understanding successful stories behind successful architecture, and will not be able to apply successful storytelling to their own use as well.

WHAT IS AT STAKE

Effective storytelling is important to the success of a firm. Our daily lives are surrounded with stories. There are different mediums and a variety of perspectives that stories are told from, but what is engaging about stories is the emotional connection that is made with the audience Stories are used everywhere in architecture from short stories creating an emotional connection with potential clients to developing and sharing design concepts. Everything tells a story and if architecture firms are not aware of the stories they are telling then they may not be telling stories that will attribute to their success. There is a relationship between good storytellers and good buildings.

>>> Stories are identification.

Stories are individual and unique because they share the perspective and history of the firm or architect by describing why they have done what they have done, as well as what they are striving to achieve. Firms use stories to identify themselves, in order connect with the audience and govern decisions. Firm profiles and philosophies start with stories and govern how the story is narrated.

Tod Williams and Billie Tsien have developed a philosophy that is specific to why their firm functions the way it does. It is intentionally vague on how to accomplish it, leaving room for concepts to be specifically modeled to each project. “We see architecture as an act of profound optimism. Its foundation lies in believing that it is possible to make places on the earth that can give a sense of grace to life—and believing that this matters. It is what we have to give and it is what we leave behind (TOD WILLIAMS BILLIE TSIEN Architects | Partners 2017).” Similar to Williams and Tsien, Steven Holl has developed a philosophy that governs his firm and story. “With each project the firm explores new ways to integrate an organizing idea with the programmatic and functional essence of a building. Rather than imposing a style upon different sites and climates, or pursued irrespective of program, the unique character of a program and a site becomes the starting point for an architectural idea (Steven Holl 2017).” These two examples show that each firm intentionally determined what their firm is about, and used that to govern and explain decisions that are part of their identity and story.

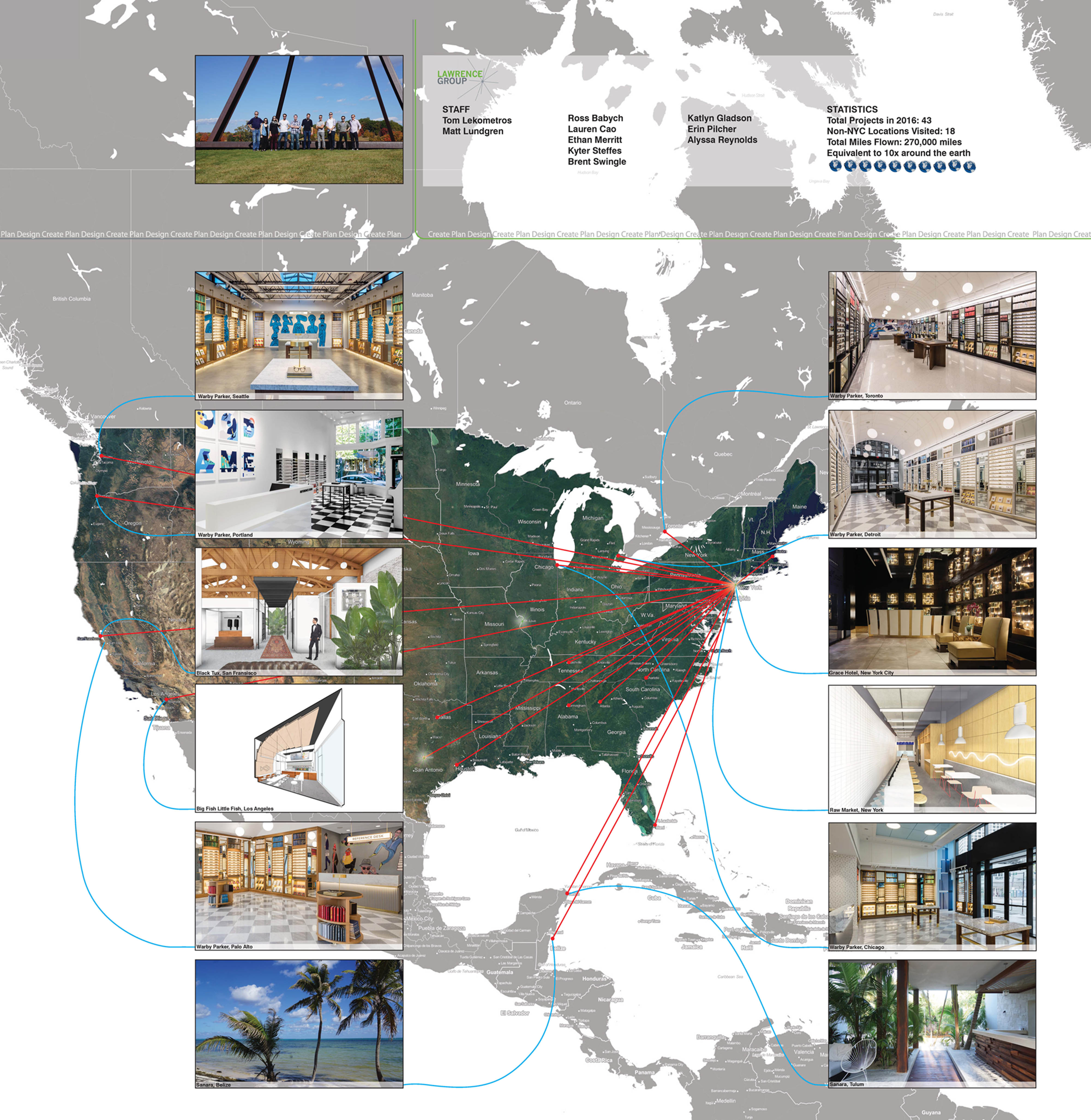

Firm profiles, values, and philosophies are not the only way to share stories; there are many avenues that can be used. This past winter the Lawrence Group held an internal conference. Different departments and offices were asked to create a poster for display during the conference. Each poster shared a story of a department or office identifying what each group did and what was unique about each one. The New York office wanted to emphasize its national and international reach by displaying images of projects from different locations connected to a giant map in the center of the poster that also displays all the non-NYC locations visited (Lawrence Group, “Conference Poster 2017).” Storytelling was used as a device to show the identity of departments and offices of the Lawrence Group.

>>> Building relationships for current and future projects.

Firms rely on stories on to gain and retain clients. Client relationships are critical to the success of a firm. Stories engage the audience/client promoting the firm and creating loyalty. No matter how architects and clients are introduced, it involves communicating a story, whether it is through an architect’s website, the principal meeting a potential client, word of mouth, or even through completed projects. Steve Jobs and Bohlin Cywinski Jackson (BCJ) are examples of a successful architect-client relationship. Steve Jobs chose BCJ to be the architect for a sales office, NEXT, in Pittsburgh. BCJ’s portfolio exhibited a wide range of work, both large and small, residential and commercial (Davis Hill 2011). “I remember when Steve first hired us, he said: ‘I hired you because you’ve done very good large buildings, and you’ve done great houses.’ If you’re doing houses, then you’re thinking about the subtleties of a building (James B. Stewart 2017).” This was a memoir from Bohlin and shows that Jobs was not just looking for an architect to do renovations, he was listening to stories, and found that BCJ was communicating a story in alignment with his values.

As Jobs returned to Apple and started to grow the company, his relationship with BCJ deepened. Apple is known for not just re-inventing but challenging what exists, and understanding how people respond to good design. Jobs knew these concepts applied equally to architecture and encouraged BCJ to do the same. If BCJ had wanted to tell a similar story then this relationship would not have worked. Today BCJ has designed more than 350 Apple stores, and is an example of how storytelling is used to create relationships (Davis Hill 2011).

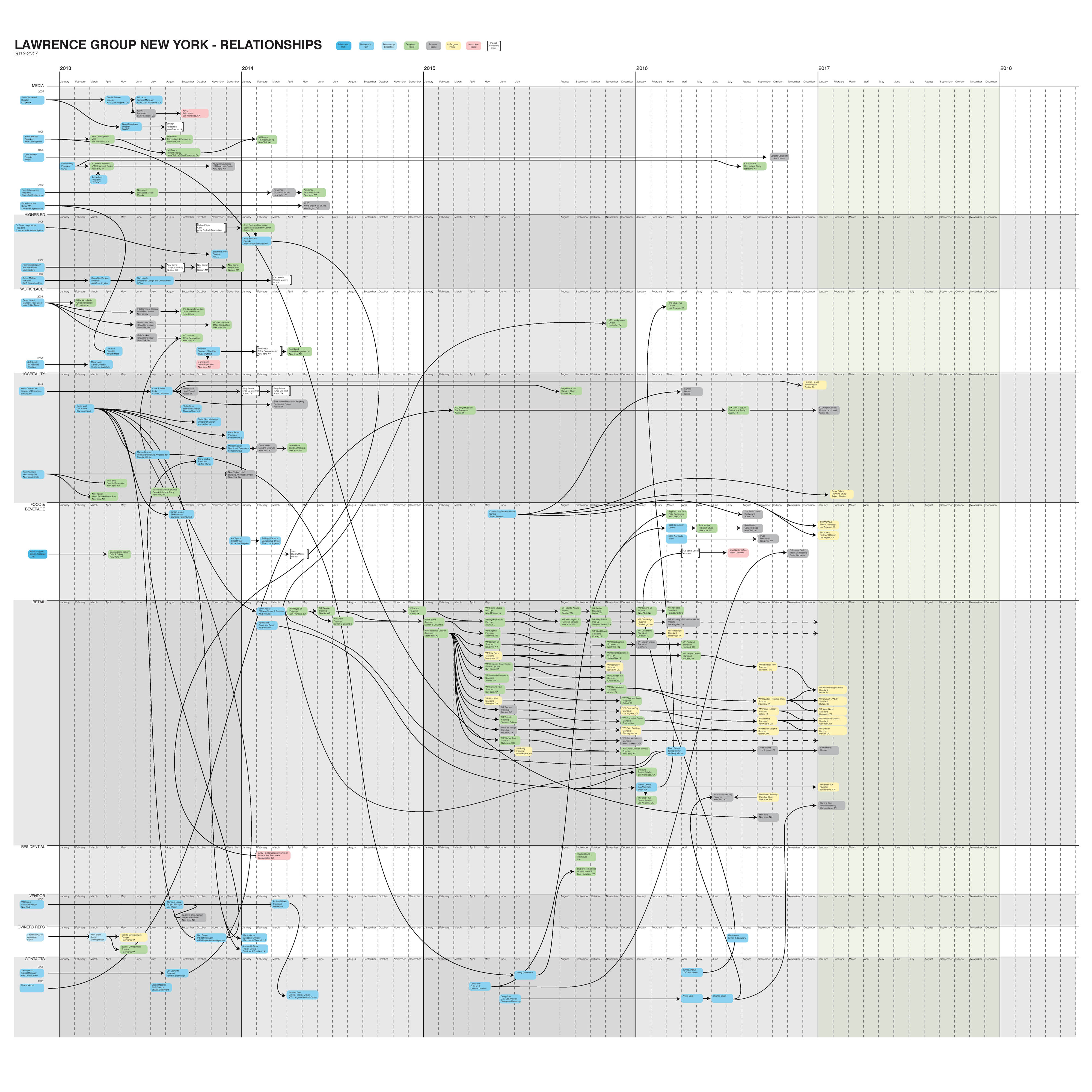

Not only are stories used to gain clients, they are used to retain clients. The Lawrence Group created a relationship diagram showing connections that were made and the projects they led to, and how those projects led to more connections or more projects. It is a narrative of project work flow within the Lawrence Group capturing critical moments.

BACKGROUND

Stories have a specific purpose and share a message or idea. Storytelling is used in many different aspects of architecture. For example, when getting projects stories engage potential clients through the architects or firm’s website, email, marketing books, architect’s RFPs, meetings and conversations, etc. Some of these forms of communication are used throughout the entire project. Once the project has begun an architect uses sketches, renderings, models, images, material samples, and presentations to communicate ideas and create a discussion with the client. Later construction documents are developed that narrate the projects story through plans, sections, elevations, and detailing that was developed at the beginning of the project, and at the same time communicating with engineers and those involved in the construction process. Once the project is completed, it shares the story on a public level, and this story adapts and changes as the function of architecture changes. Stories are constantly used in architecture and it is the architect’s responsibility to realize that stories are found in many aspects of architecture and it is also the architect’s responsibility to curate stories that support the overarching outcome.

CLAIM AND ARGUMENT

By analyzing the effect storytelling has in architecture, we can better understand its value and develop a platform for discussing storytelling. For the purposes of this paper, storytelling is composed of three primary components: audience, moral, and context. If there is no audience, then there is no reason to tell a story. At the same time, understanding the moral of stories is important because they are shared with the audience. Additionally, there are many perspectives and many ways to receive a story. Being aware of the audience’s perspective, stories can be adapted to be effective to the audience.

WHO IS THE AUDIENCE

A well told story has no effect if it is not heard. Stories are designed for audiences. In architecture there are two audiences – the client and the user. Understanding who the audience is makes it easier to understand the perspective of the architect, client, and user, in order to craft effective intentional stories.

>>> The story of the client.

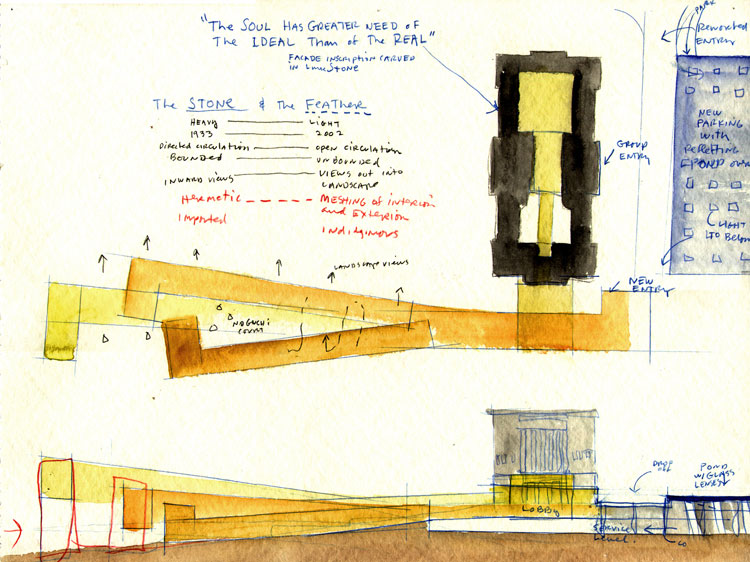

Clients have a story and vision. Architects need to provide design solutions that capture and enhance the client’s vision. In 1999 a juried competition was held for the expansion of the Nelson Atkinson Museum in Kansas City, MO (Steven Holl Architects 2007). The original Neoclassical building was very formal being built in 1933. In the competition most of the architects responded very formally to the site and building. However, Steven Holl’s entry was different because he proposed the idea of creating a distinction between the two buildings — the original architecture and the new architecture (Steven Holl 2017). The existing museum he considered the stone because it was older with a heavy appearance, and the addition he considered the feather because it was newer and lighter in appearance (Steven Holl Architects 2007). By keeping it distinct and separate, the original building did not lose its integrity and the new addition was given the opportunity to narrate its own story. Holl describes it as “lightweight glass lenses scattered throughout the landscape, framing sculpture gardens (Steven Holl Architects 2007),” The jury selected Holl’s proposal and completed the project in 2007.

Holl’s proposal was chosen not necessarily because it was abstract and different, or even because it was the most in line with the clients expectations, his proposal was chosen because he listened to the story that they were wanting to tell and he realized that the story they were wanting to tell did not align with how they thought the architecture should respond. He then made a proposal that aligned with the story they were wanting to tell. Holl’s story shows why it is important to understand the client and the story they want to tell. In a successful project the client’s values will be clearly represented. It is the architect’s responsibility to decipher what these values, goals, and objectives are and understand that they may be different from what client initially expresses.

>>> The users story.

Depending on the project, the general public and users of the space are an audience that are equally important as the client. An example would be designing a school that facilitates student learning, encourages teacher collaboration, and is compatible to host community events. Because many buildings are designed for users that are not part of the design process, it is important to understand how the general public will receive and interpret the story. An architecture project is subject to different opinions and viewpoints, even the Nelson Atkinson Museum had mixed reviews by the public. However, since it has been built, the public sees how it functions, and it has become an iconic architecture work and the public has grown to appreciate it (David Frese 2017). Even though Holl’s proposal was based on the story that the clients wanted to tell, he designed it with the intent of serving the general public, keeping in mind how the spaces would function, being sensitive to its pragmatic function and aesthetic. Holl’s proposal focused on a story which captivated the client, and embraced the public.

>>> The architects story.

Although architects are the ones who curate the story, they are just as much a character and audience as the client and user. The projects which they complete reflect back on the firm and become chapters of their own story. Therefore, understanding the story or vision of an architecture firm reveals the foundation and philosophy that decisions are based on. Holl’s philosophies were just as integrated into the Nelson Atkinson museum as the philosophies of the client and user. Through the idea of a feather and stone he was able to integrate the two architectural types, old and new, into one design.

>>> Curating a story is like playing pool.

As demonstrated, there are typically three parties involved when working on a new project: the architect, the client, and the user. Each party have different interests within the project. Successful firms curate their audience by aligning similar goals and values between the architect, client, and user. This is similar to the game of pool. Imagine trying to shoot and get two balls in with one shot. In this case, the white ball represents the architect. The closer the balls are in alignment, the easier it is to get two in one shot. Although, the goals and values of the architect, client, and user do not have to be identical, it is the architect’s job to find ways to align the goals so that they compliment each other. Relationships brought into alignment are rewarding and successful for everyone. The goals of the client and user are successfully met by the architect, resulting in another chapter in the architect’s story (Simon Sinek 2011).

STORIES

Stories create emotional connections, facilitate relationships, and become a testament to potential clients.

>>> Emotionally connecting with the audience.

Emotions are powerful and sometimes overwhelming. Thoughtful storytelling will connect clients and users on an emotional level. Emotions cement the audience in a dogmatic manner which can defy logic. The story of the American Folk Art Museum in New York City designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien is one with several important moments that emotionally connect the audience from beginning to end. The first moment happened when the project began. The American Folk Art Museum project had been narrowed down to three candidates who were invited to be interviewed. Instead of going into the interview with models like their competitors, Tod Williams Billie Tsien went in with nothing but a proposal, yet connected at an emotional level with the jurors, showing their desire to understand the project better (Karrie Jacobs 2013). The second moment happened after the project was finished. The American Folk Art Museum was named one of the “Best New Building in the World in 2001.” Its timely completion after 9/11 was inspiring, connecting it emotionally to the city of New York. The last moment that the American Folk Art Museum emotionally connected with the audience happened when it was decided that it would be demolished for the expansion of the MOMA, twelve years after it had been completed. To some it had become an “architectural gem” in New York City and it became a heart-breaking story (Adelyn Perez 2010). Successful stories not only share moral values but connect with the audience on an emotional level.

>>> Developing trust and respect with the client.

When an architect’s philosophy connects with an audience on an emotional level, trust and respect become the by-product. This area is a crucial element to an engaging relationship. When Tod Williams Billie Tsien conveyed their desire to understand the client’s needs on a higher level, they gained the trust and respect on an emotional level and were awarded the contract

>>> Stories become a testimony.

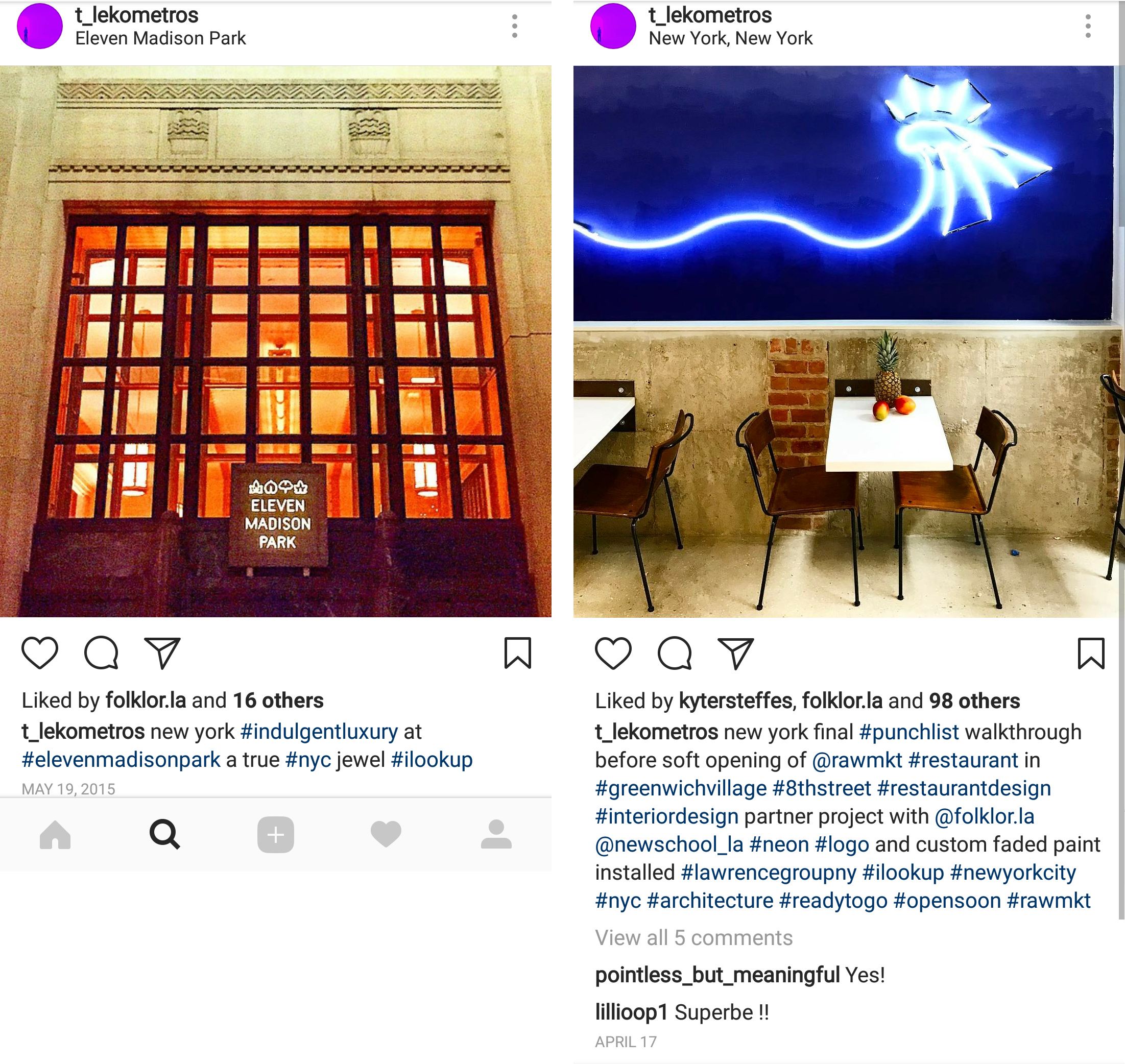

Figure 10: Lekometros, Tom. Raw Market, April 17, 2015, Photography.

The relationship diagram mentioned previously created by the Lawrence Group shows how well propagated stories become a testimony to potential clients. The Lawrence Group and Folklore, a consulting agent for creating brands, met on Instagram when Folklore decided to follow Tom Lekometros, principal of the New York office. They shared mutual interests and appreciated each other’s posts. A few months later, Folklore introduced the Lawrence Group to Scott Schubinar, who was in the process of starting a new restaurant – Raw Market. A relationship formed and the Lawrence Group became the architect for Raw Market which opened in Spring 2017 (Lawrence Group, “Relationship Diagram” 2017). This example shows how stories are testimonies. Lekometro’s Instagram became a way to tell stories and connect with an audience, which may include potential clients or people who will recommend potential clients, as was the case with Folklore and Raw Market.

HOW IS THE STORY TOLD

The way stories are told is as important as the storyline. How stories are told affect how they are received. Literary devices, vocabulary, presentations, and viewpoints are elements that enhance and clarify what and how the story is told.

>>> Engaging the audience using literary devices.

http://www.vagabondish.com/photo-under-venetian-sunset-italy/

Regardless of what stories share, if they are not told in an engaging manner they will lose the attention of the audience. Literary devices are important because they enhance stories, engage the audience, add a humanizing touch, and make stories memorable. There are many literary devices that can be used: metaphors, similes, and the like. In architecture, additional devices can be found in presentations, sketches, renderings, models, etc. Invisible Cities is a fictional book written by Italo Calvino that artistically captivates the audience through his poetic description usage of literary device. Marco Polo was asked by the emperor, Kublai Kahn, to visit cities in the empire. Polo describes a total of fifty-five unique cities. Midway through the story it is revealed that Polo had been describing Venice the entire time (Italo Calvino 1972). Calvino used multiple literary devices to describe the cities in variety of ways, each an analogy of Venice. Invisible Cities uses literary devices through dialect to describe the city.

Figure 13: Darden, Douglas, Discontinuous Genealogy, 1993, Sketch.

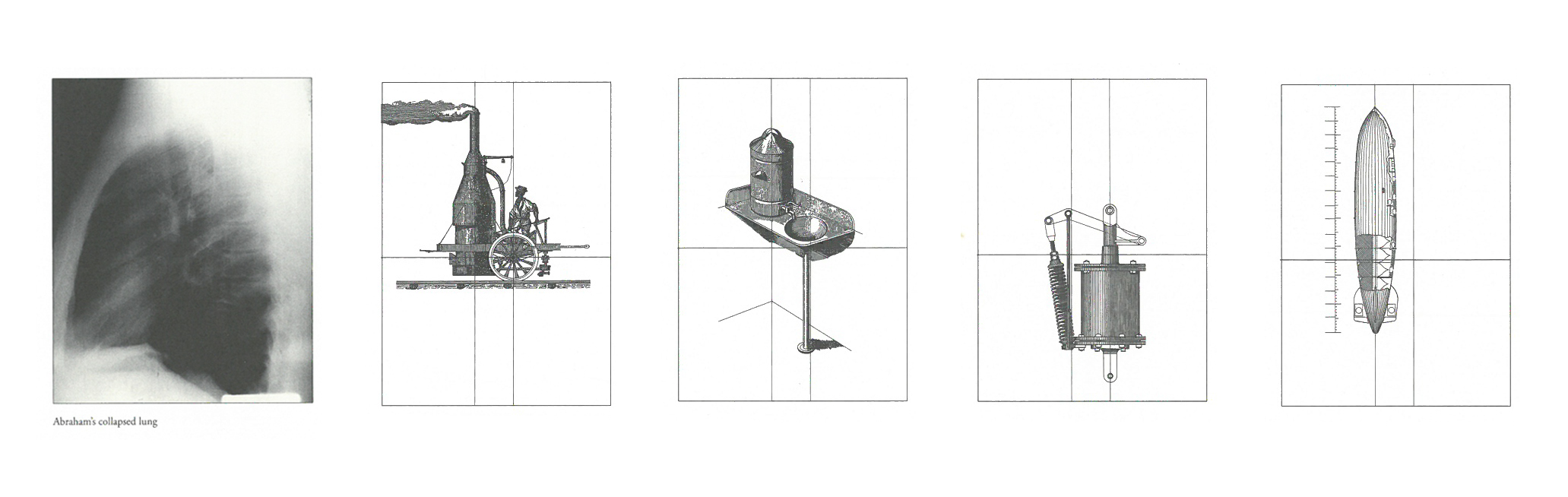

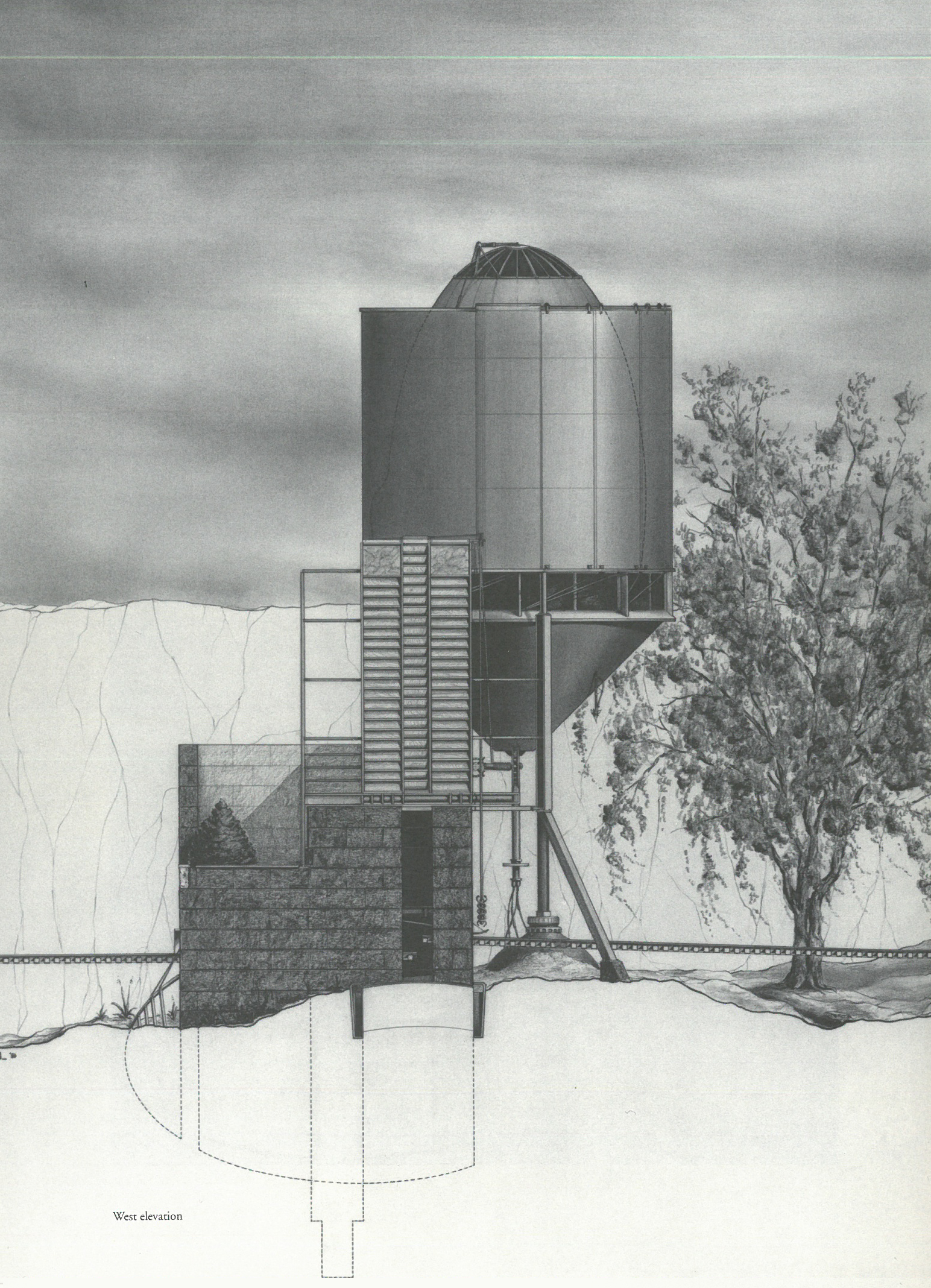

Condemned Buildings is a book in which Douglas Darden presents ten fictional projects. It differs from Invisible Cities because it uses drawings and images, as well as a dialect to tell the story. The last project of the book is the Oxygen House. Darden was commissioned by Burden Abraham, who worked on railroads for a living. One summer there was a train derailment due to excessive amounts of rain and Abraham was injured in the accident and suffered a collapsed lung. Several years later Abraham bought the land that the accident happened on. He commissioned Darden to design a house to live in and to be buried in at death. Darden responded by designing the house to undergo metaphorical operations. Four operations when he was alive, and four operations after he died. Detailed drawings and inspirations are included in his narrative, as well as an x-ray of his collapsed lung, and a letter from Abraham to Darden (Douglas Darden 1993). It is told in an engaging manner, does not overburden the listener/reader, and is presented with text and visual cues. The point is that literary devices are not just limited to verbal and written stories, they can be found in images and architectural projects.

>>> Poetically communicating the story.

Well told stories are not just limited to the innovative use of literary device, but also rely on poetic interpretation using key words, unique and captivating phrasing, and ideas that capture the audience. Once there was a world-renowned architect commissioned in 1956 to design a pavilion for a very special event in 1958. The world was experiencing a crossroads, transitioning into the technology age that would begin 40 to 50 years later. In response to the changing world at that time the architect determined that he “…wanted to mark the end of exposition, and the beginning of another, the electronic [exposition] (Marc Treib 1997, x).” He determined that the best way to communicate this idea was to make the architecture of the pavilion an electronic poem. He collaborated with visual and musical artists to embody this idea. The result was a video projected into the space of the pavilion which was accompanied by specially composed music. The architect combined electronic sound and imagery to create a space which was the electronic poem. Most people responded positively to the project. However, the project did not have a happy ending. On January 23, 1959 at 2:00 pm the entire structure was imploded, as it was designed to be a temporary project (Marc Treib 1997). This is the story of Le Corbusier designing the Phillips Pavilion for the World’s Fair in Brussels, and shows how Le Corbusier was able to captivate his audience with his unique presentation of ideas and creativity that knows no bounds.

https://discorgy.wordpress.com/2008/08/04/varese-xenakis-le-corbusier-poeme-electronique-1958/

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/329748003942679703/

OBJECTIONS

>>> Misunderstood and falsely represented.

Many stories in architecture are ones that highlight success rather than focusing on failures. There is a problem when stories are told so seamlessly that they do not show the struggles, or give an accurate demonstration of teamwork. Parts need to be omitted to give clarity, however, omitting parts becomes dangerous when it does not meticulously represent what happened. Space Calculated in Seconds is a book written by Marc Treib on the Phillips Pavilion designed by Le Corbusier and is a captivating story because there is an honesty in the way it was written. Treib makes it very clear in the book that he does not want to “… advance Le Corbusier as the sole generating genius, under whose aegis the project was shaped from concept to detail (Marc Treib 1997, xvii), ‘but that Le Corbusier ‘….benefited from dedicated and talented collaborators (Marc Treib 1997, xvii).” He realized that his collaborators were as equally important to the project and story as Le Corbusier. It would have been a very different outcome if they had not played the part they did. Treib not only emphasized the many characters of the story, but also showed the struggles and challenges that were faced. There were challenges in communication, differences of opinions, site constraints, material limitations, and deadlines, just to name a few. Stories involving challenges are relatable and touching. If Treib had told the story of the Phillips Pavilion without emphasizing the difficulties a completely different story would have been told and Le Corbusier would have been presented as an architecture god held at a higher standard and completely unattainable to the average human being. There can be a danger when telling stories that do not give an accurate account of teamwork and challenges that were faced and overcome. Giving an accurate account of teamwork gives credibility to the story and talks about the challenges relating to the audience.

>>> Hopelessly defining stories.

One of the challenges of storytelling is that there is not a definition or standard of good stories and is subject to differences of opinion. Some stories are successful from one perspective, but a failure from a different perspective. The design of the Richard’s Medical Research Laboratory completed in 1961 by Louise Kahn exemplifies this notion. Kahn had created an articulation of servant and served spaces, innovatively lit the structure, and integrated spatial, structural, and utility elements. It was well received in the architecture community and critics praised it claiming that the “… building represented a significant turning point in architecture (Richards Medical Center)”. However, it was absolutely detested by the scientific community who occupied the space. They claimed that the building “…lacks privacy, has too much exposure to sunlight and is not suitable for lab experiments (Karissa Rosenfield 2016).”

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/540713498985201481/

How would you determine if the short story about the Richard’s Laboratory was good or bad? Standards are developed using an individual’s worldviews, values, personal experience, and knowledge. Understanding that everyone has different standards is important to acknowledge, but can be challenging when designing a story to fit the audience. People have different perspectives based on personal experience, while these differences are not necessarily good or bad, they add color to the experience.

THE PRESENTATION

“As I began giving the presentation the next day my heart was pounding like a drum. This presentation was a unique opportunity for the firm, which was additional stress. Going through the presentation I clearly articulated the story. The marble complimented the colors of the space and made a historical reference to monumental buildings in the city. The reflective stainless steel would add a minimalistic touch while emphasizing the simplicity that the client valued, and the blond wood would reflect the gold hidden throughout the site while adding warmth to the overall design. I finished the presentation and anxiously held my breath waiting for their response…”

SUMMARY

Architecture is filled with many interesting stories and understanding the elements of a well told story is important. Storytelling is broken into three components: the audience, the philosophy, and communication. A well told story has no effect if not heard, therefore, understanding who the audience is is important so that effective well-crafted stories can be told. It is important to understand what the moral of the story is. Well told stories function as a catalyst between the storyteller and the receiver, they play on emotions, create and deepen relationships, and become a testament to potential clients. Understanding the way stories are told is equally important to the story that is told. A story could be told one way but received many ways. When analyzing storytelling there are two things that we need to be aware of. First, stories can be misrepresented or misunderstood. Storytelling can diminish the effects of team work or make something look effortless, even though it was quite difficult. Secondly, the definition of good stories vary from person to person. Architects are just storytellers and there is a connection between good storytellers and good buildings. Stories are everywhere in architecture, and architects need to be aware and intentional about the stories that are being communicated.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, storytelling not only communicates effectively with all members during the design process, but it opens up a channel for sharing unique ideas that build off each other, enhancing relationships and projects in a positive and engaging manner.

Bibliography

Calvino, Italo. Invisible Cities. New York, NY: Mifflin Harcourt Publishing, 1972.

Darden, Douglas. Condemned Buildings. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993.

Frese, David. “10 Years After Opening, New Challenge for Bloch Building.” Kansas City Star (Kansas City), June 07, 2017, Visual Arts sec.

Hill, David. “Steve Jobs: “A Great Client”.” Architectural Record 199, no. 11 (November 2011): 21. Accesses March 20, 2017. http://web.b.ebscohost.com.er.lib.k-state.edu/ehost/detail/detail?sid=1ec229fd-cc91-4e3d-a762 633d744830eb%40sessionmgr120&vid=0&hid=118&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=70840880&db=aph

Jacobs, Karrie. “Inside Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects.” Architect Magazine. June 18, 2013. Accessed March 16, 2017. http://www.architectmagazine.com/awards/aia-honor-awards/inside-tod-williams-billie-tsien-architects_o.

Lawrence Group. “Relationship Diagram.” January 2017.

Perez, Adelyn. “American Folk Art Museum / Tod Williams Billie Tsien.” ArchDaily. May 30, 2010. Accessed April 30, 2017. http://www.archdaily.com/61497/american-folk-art-museum-tod-williams-billie-tsien.

Quirk, Vanessa. “Confirmed: American Folk Art Museum to Be Demolished.” ArchDaily. January 08, 2014. Accessed April 30, 2017. http://www.archdaily.com/465308/confirmed-american-folk-art-museum-to-be-demolished.

“Richards Medical Center.” GreatBuildings.com. Accessed June 27, 2017. http://www.greatbuildings.com/buildings/Richards_Medical_Center.html

Rosenfield, Karissa. “Louis Kahn’s Notorious Richards Laboratory Restored.” ArchDaily. January 12, 2016. Accessed June 3, 2017. http://www.archdaily.com/780260/louis-kahns-notorious-richards-laboratory-restored-to-its-original-essence.

Sinek, Simon. Start with Why. New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2011.

Stewart, James B. “A Genius of the Storefront, Too.” The New York Times (New York City), October 16, 2011. Accessed March 20, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/16/business/steve-jobs-a-genius-of-store-design-too.html

Steven Holl Architects. Accessed April 30, 2017. http://www.stevenholl.com/.

Steven Holl Architects. Steven Holl Architects’ light-filled Nelson-Atkinson Museum of Art to open on June 9. 2007. http://www.stevenholl.com/.

Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects | Partners. Accessed April 30, 2017. http://www.twbta.com/studio/philosophy

Treib, Marc. Space calculated in seconds: the Philips pavilion, Le Corbusier, Edgard Varese. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University press, 1997.